“Now, may our God be our hope. He Who made all things is better than all things. He Who made all beautiful things is more beautiful than all of them. …Learn to love the Creator in His creature and the Maker in what He has made.“(St.Augustine of Hippo, Commentary on Psalm 39).

“..and there is no doubt of the supreme mathematical beauty of Einstein’s general relativity.” (Roger Penrose,The Road to Reality).

The Einstein field equation, shown above in abbreviated form, is considered by most physicists to exemplify the most beautiful of all physical theories, that of general relativity. What are the requirements for a beautiful theory and how do these manifest, as St. Augustine has it, the Creator’s handiwork? The beauty is displayed in the mathematics of the theory, in the equations that relate it to the world. A first requirement is generality/profundity–the equation has to be the basis for understanding a very broad and deep range of phenomena–as Einstein said,

“I want to know how God created this world. I am not interested in this or that phenomenon. I want to know His thoughts; the rest are details.“ (as quoted by A.Zee in “Fearful Symmetry”)

A second requirement is conciseness–what theoretical physicists would call elegance–Hemingway versus Faulkner or James. An equation that covers a page or so of symbols may be important and general, but it would not be beautiful. Much is summarized in the tensor notation of the general relativity field equations, but this beautiful form did not come easily. It was not the result of sudden inspiration, unlike the lay view of how great science is done, but the result of eight years of dedicated effort, as Professor John Norton so well describes, in his discussion of Einstein’s notebooks: “General relativity was an achievement of creative imagination.”

|

| A page from Einstein's notebook on the formulation of general relativity-- see linke above to Prof. Norton's web-page |

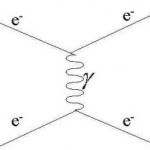

There are other beautiful equations: Dirac’s equation combining quantum mechanics and special relativity, which led to the discovery of anti-matter and the theoretical basis for particle spin. And it was Dirac who said “It is more important to have beauty in one’s equations than to have them fit experiments”, a sentiment with which I am not entirely in agreement.

|

| Dirac's Relativistic Equation for the Free Electron |

In this connection, both the theory of general relativity and the Dirac equation have been confirmed experimentally. General relativity was confirmed initially by the bending of light during a solar eclipse and by its quantitative explanation of the advance in the perhelion of the orbit of Mercury (as well as many other confirmatory experiments since then).

The Dirac equation explained the existence of electron spin and predicted the existence of the positron (a positively charged electron), found experimentally some four years later.

There is one other beautiful equation I want to mention, which in my opinion is as important as the two above: Boltzmann’s equation for entropy (S) in terms of thermodynamic probability (W),

There is one other beautiful equation I want to mention, which in my opinion is as important as the two above: Boltzmann’s equation for entropy (S) in terms of thermodynamic probability (W),

S= k logarithm(W)

(k is the Boltzmann constant). |

| Boltzmann's Tombstone; the Equation S= k logW is at the top and the bust is of Boltzmann |

This equation (engraved on his tombstone–see picture–and tattooed on my younger son’s arm) justifies the Second Law of Thermodynamics (the scientific version of Murphy’s Law: the universe is running down, no matter what

or, you can’t unscramble eggs without doing work),

a physical law that, according to Einstein, will still be true many hundreds of years from now, even if all other theories are invalidated.

or, you can’t unscramble eggs without doing work),

a physical law that, according to Einstein, will still be true many hundreds of years from now, even if all other theories are invalidated.

GOD, BEAUTY AND MATHEMATICS.

Given that mathematics and mathematical physics have elements of beauty, what does this have to do with God? The notion that mathematical truths are Divine is ancient history, going back to Pythagoras and Plato in ancient Greece. Augustine, and more recently Cantor (19th Century), argued that infinity is a manifestation of God’s ineffability.

Why is science is explained mathematically? Or, as the renowned mathematical physicist, Eugene Wigner, puts it in his article, whence “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences"? The question was, of course, answered some 500 years ago by Galileo:

Why is science is explained mathematically? Or, as the renowned mathematical physicist, Eugene Wigner, puts it in his article, whence “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences"? The question was, of course, answered some 500 years ago by Galileo:

“The laws of nature are written by the hand of God in the language of mathematics.”We want to understand the world and to recognize, as Scripture declares, that God looked on His Creation and saw that it was good. When you see children playing with toy cars or other objects and arranging them neatly in a line, you see the first beginnings of a desire for order and sequence.

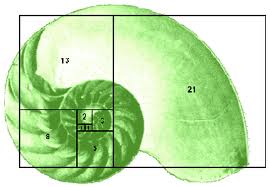

Mathematics has an intrinsic beauty that is not constructed by our minds, but is discovered by us.

|

| Nautilus shell pattern illustrating the Fibonacci Sequence (from "Heritage Math", by Savannah Morrow) |

I want to emphasize that the beauty of pleasing proportion comes from more than symmetry. Symmetry can be an element of beauty, but it neither a necessary element nor always a sufficient element. It is the apprehension of order, an order that appeals to our intellect, that is the core of beauty. This appeal to intellect distinguishes beauty from that which is simply good, according to St. Thomas Aquinas:

“The beautiful and the good are the same in the concrete existent (in subjecto), for they are based on the same thing, namely on the form. For this reason the good is approvingly called the beautiful. Yet, they differ in their intelligibility (ratione). For the good appeals to the appetite; indeed, the good is what all desire. So, it has the intelligible nature of an end, for appetite is sort of a motion toward a thing. On the other hand, the beautiful appeals to the cognitive power: for things that give pleasure when they are perceived (quae visa placent) are called beautiful. (emphasis added). St. Thomas Aquinas,Summa Theologica

Aquinas also requires that which is beautiful be profound (he uses the term “large” or “big” but I think that can be construed as profound, as applied to beauty in science): “Beauty is found in a large body”.

I think Aquinas also shows the connection between Beauty and God in his Fourth Way, (the fourth of five ways of demonstrating the existence of God), which can be stated using the conclusion of the syllogism given in the link, “Thus, there is something that causes the being and goodness of every perfection in all things, and this is God.”

|

| The "Big Trees" of Yosemite Park (note the small size of the person in the foreground.) |

And all this became reinforced, later on when I became a Catholic (but more of that in a later blog) and saw that all of science was realized in Psalm 19a, “The Heavens declare the glory of God.”

Twitter

Facebook

Link